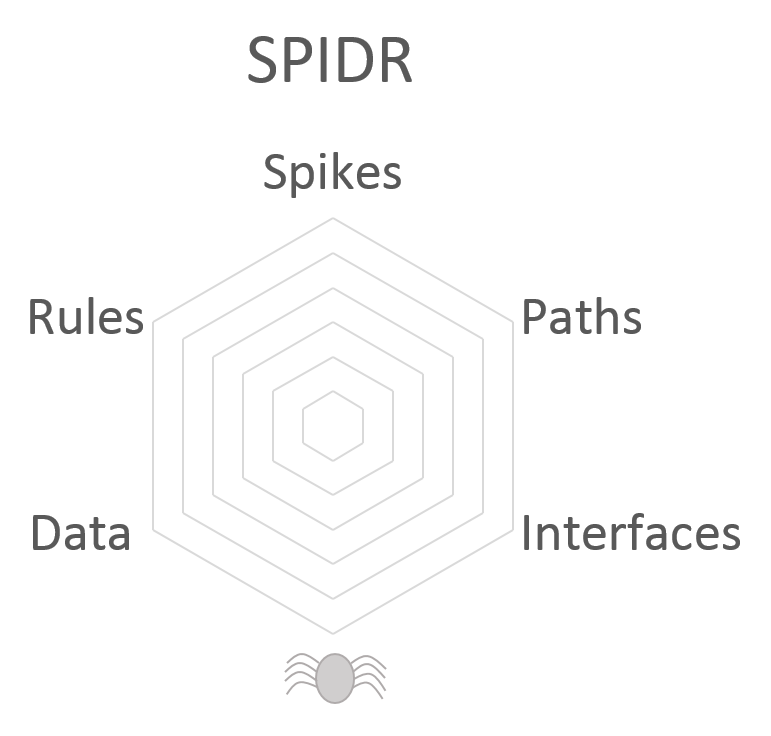

Some time ago I discovered an interesting and helpful method for splitting user stories into more lightweight stories more easily and effectively. Agile coach and co-founder of the Scrum Alliance, Mike Cohn, noted that "almost every story can be split with one of five techniques". He summarizes these five techniques under the acronym "SPIDR".

Firstly there are two types of user stories that are fundamentally different from each other:

- User stories that are extremely large from the ground up and cannot be split, but which also occur extremely rarely.

- Compound user stories, which contain many smaller stories and can thus be split.

Split compound user stories

According to the INVEST principle, the requirement for a user story is that it must be “small enough” or have the right size. A user story should be sufficiently small that 6–10 of them can be done in a sprint. Of course this also depends on the speed of the development team. To achieve this goal in principle, a large story must be split accordingly.

There are now several techniques and tools that can be used to spit such user stories. For example, Richard Lawrence presents a comprehensive poster that guides the viewer through a process that should help to split user stories. In the following, however, I would like to introduce you to the simple and fast SPIDR method from Mike Cohn. He summarizes five techniques with which almost every large user story can be divided.

Spikes

Spike is a term used in agile software development. Spikes are small, prototypical implementations of a functionality that is typically used for the evaluation and feasibility of new technologies.

This method involves investigations and building knowledge. It should be used if other SPIDR methods have not worked well. With the help of such newly acquired knowledge, some stories can then be better understood and possibly split more easily. This method, however, is relatively abstract and therefore harder to apply than the remaining methods.

Paths

If there are several possible alternative paths in a user story, one option is to create separate user stories from some of these paths. It is not absolutely necessary to write a story for each individual path, just where it makes sense. For example, let's take a user story in which the user wants to be able to pay for purchases in an online store. There are now two possible paths: payment with a credit card or payment with Paypal. Payment with a credit card can theoretically be further subdivided, but you need to weigh up whether it makes sense for each type of credit card to have its own story. The overriding task of paying for purchases is, however, divided well into the two alternatives mentioned. Thus the newly created stories are smaller and more easily estimated.

Interface

Interfaces in this context can for example be different devices or device types, such as smartphones powered by iOS or Android. User stories can also be split in terms of this diversity. Let's stick with the example of different operating systems: in a project, for example, there may be user stories that relate exclusively to the use of Android devices, or others that focus on web browsers. To avoid making stories too large and comprehensive, you should ask yourself which devices or interfaces you want to develop. Perhaps the first development result should only refer to iOS devices, because of the probably larger target group.

Data

Another technique for splitting user stories can be used when the initial stories refer only to a sub-range of the relevant data. Take the example of a website intended to attract tourists to a particular city. If it is a city known for its museums, for example, the first story could include information about the different museums in this area. A subsequent story could include various tourist tours through the city, and another deal with outdoor activities.

Rules

Business rules or technological standards can be another splitting factor. Take the example of online purchase of cinema tickets. There are often constraints that are for example based on business requirements of the respective cinema, such as an online purchase limit of a maximum of five tickets per e-mail address.

With this story it would be conceivable that the development team omit this restriction, allowing every visitor to buy as many tickets as they wish. The restriction could then be added in a second iteration step. Incremental delivery such as this means that initial stories are not immediately implemented completely, but instead are delivered in several smaller steps. Sometimes it makes sense to neglect technical specifications or business rules, if by doing so you can more quickly achieve a presentable result that satisfies the user or client. Omitted stories can be retrieved at a later date.

Small user stories – easier realisation

User story splitting is not always easy: many beginners tend to leave their stories overly comprehensive and much too big. But when it comes to refinement with the development team, and ultimately to the implementation of the stories, it can soon become clear that much smaller stories must be produced. In my previous blog post on writing (good) user stories I maintained that a story should be “estimatable” and “small”. This is more likely to happen if you know how to divide a large story. And exactly as for writing user stories, practice makes perfect.

You want to know what else makes a good user story? You can read about it in my blogpost "What are (good) user stories?".

Comments